March 20, 2018 – A first of its kind study shows typical interruptions experienced by on-call radiologists do not reduce diagnostic accuracy but do change what they look at and increase the amount of time spent on a case.

The implication of the finding is that as radiologists contend with an increasing number of workplace interruptions, they must either process fewer cases or work longer hours - both of which have adverse effects in terms of patient outcomes, said Trafton Drew, the study's lead author. They also may spend more time looking at dictation screens than reviewing medical images.

"In radiology, there is a growing recognition that interruptions are bad and the number of interruptions faced by radiologists is increasing," said Drew, an assistant professor of cognitive and neural science in the University of Utah's Department of Psychology. "But there isn't much research at all on the consequences of this situation."

The Journal of Medical Imaging published the study online; it will appear in its July-September issue. Co-authors are: Lauren Williams, Department of Psychology, University of Utah; Booth Aldred, Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, University of Utah/Austin Radiological Association, Austin, Texas; Marta Heilbrun, Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, University of Utah/Emory University Hospital; and Satoshi Minoshima, Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, University of Utah.

Other research has shown that an on-call radiologist typically receives an average of 72 phone calls during a typical 12-hour overnight shift. An interruption, for example, might involve conferring with an emergency department physician about a new patient.

In the study, experienced radiologists were given a list of pre-selected, complex cases to read and were then interrupted by a telephone call that played a pre-recorded message from another physician that asked them to evaluate a different patient's case. The study is the first to experimentally manipulate whether specific cases were or were not interrupted.

"This let us look at the effect of the interruption without worrying about whether a particular case might have been more difficult than others," Drew said.

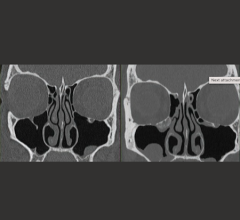

The researchers used eye-tracking software to determine what radiologists were looking at before, during and after being interrupted. Drew and his team anticipated that an interruption would lead to errors in interpreting images, but "it didn't change the error rate at all."

However, radiologists spent several additional minutes overall on the case they were reviewing the first time they were interrupted. They also spent more time looking at a dictation screen, suggesting the screen serves as an external memory aid, and less time viewing medical images after the distraction.

"That suggests they had to recollect what they looked at and the dictation screen helped them do that," Drew said. "Given that radiologists spend about 10 minutes on a complex case, we think this could be a big problem in the aggregate. They can go back to what they were doing but there is a significant cost there in terms of time. If we could do something to reduce the interruptions it could really help radiologists out."

Some radiologists who participated in the study noted that the interruptions used by researchers were benign compared to the disruptions they often experienced in the workplace. Drew and his colleagues hope to follow up on this concern in future research.

"If radiologists truly spend less time on medical images and more time on dictation after being interrupted, it may explain why prior research has found that shifts with more interruptions tend to have more uncertainty about patient diagnosis," Drew said. "If it takes some period of time for the radiologist to reconstruct what he or she saw prior to the interruption, it might actually be good practice to take a little longer on cases when they are interrupted. Ultimately, this means that interruptions will either lead to more potential for error or fewer cases being seen by the radiologists."

Watch a video on the topic here.

February 20, 2026

February 20, 2026