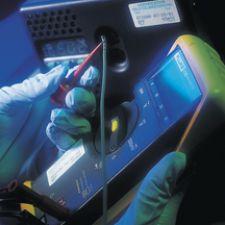

Final RO/DI rinsing step in the reprocessing of EP catheters removes bio-burden and pyrogens.

Even a representative from one of the nation’s leading single-use device (SUD) reprocessors says he understands the support behind a patient consent bill recently introduced in Massachusetts.

In fact, Don Selvey believes most Americans would say “yes” if asked, point blank, whether they would prefer to be informed before an SUD is reused on them — especially one that pierces the skin or enters the bloodstream.

“But when you sit down and explain what’s really going on, people get much more reasonable much more quickly,” he said.

Selvey is the vice president of Regulatory Affairs and Quality Assurance for Ascent Healthcare Solutions (Phoenix, AZ), a company formed this year from a merge between Alliance Medical Group and Vanguard Medical Concepts.

Before the merge, the companies collectively reprocessed more than 40 million SUDs for over 1,700 healthcare facilities nationwide.

If Senate Bill 1321 is passed as-is, Massachusetts will be the first state in the country to require its patients to provide written consent prior to having a reprocessed SUD used in their medical procedures.

The added burden to hospitals could significantly slow the booming reprocessing business, especially if other states follow suit.

President of the Massachusetts Medical Device Industry Council (MassMEDIC) Tom Sommer says the bill is a step toward ending a practice that jeopardizes patient safety.

“We believe that patients should have the right to make informed decisions about the medical care that they receive to protect themselves from unnecessary risk,” he said.

But Selvey sees it differently.

“There’s no public heath issue here,” he said. “If there was, I assure you that the FDA would have addressed it.”

The Third-Party Boom

“Hospitals have been doing some level of device reprocessing for a long time,” Selvey said, referencing a medical text published in 1919 that mentions the technique.

The recent controversy began in the early 1980s when original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) started labeling certain devices as single use only.

“Hospitals were looking at these and saying, ‘now wait a minute, this is exactly the same device we were resterilizing last month, and now [the OEMs] are saying we should use it once and throw it away?’” Selvey said.

Many hospitals decided to keep reprocessing the devices as a cost savings measure, and after much legislative and media scrutiny the FDA presented a guidance document in 2000 to regulate the practice.

“It simply said if you’re going to do it, make sure you do it correctly,” Selvey said. “And all it did was shift the burden to whomever was doing the reprocessing and said whatever it is that you’re doing, prove that it’s adequate.”

Struggling to keep up with the paperwork and legalities of the new requirements, most hospitals either turned to third-party vendors or stopped reprocessing SUDs altogether.

According to Selvey, a majority chose the former.

“Honestly, it was a tremendous boom,” he said. “We grew phenomenally.”

He estimates that the reprocessing business has between quadrupled and quintupled in the past six years, putting the number of hospitals that use third-party vendors today at around 90 percent.

A Barrier to Devices

Joe Kiani is vice chair of the Medical Device Manufacturers Association and CEO of Masimo Corp. (Irvine, CA). He says the bill can “only be good for patients and hospitals.”

“I certainly would like to know before I’m getting a procedure whether the device they’re using on me is designed for single use,” he said. “I’d like to be given that choice and some time to think about it.”

Both Kiani and Sommer contend the devices are labeled “single use” for a reason.

“They are not designed to withstand repeated cleaning and sterilization,” Sommer said. “Many of the SUDs often have unique features…that can make access difficult, create barriers to cleaning and provide a surface on which blood, tissue and other organic matter can accumulate.”

But Selvey says the FDA doesn’t mandate the “single-use” label — and while he supports patients being active in their own healthcare decisions, required consent would needlessly create a barrier to using the devices.

“If a surgeon is [performing an operation] and discovers he or she really needs a certain device, under this particular legislation, that surgeon would not be able to choose the device if it is reprocessed,” he said.

The real reason behind the bill is financial, according to Selvey. He says there are not enough documented cases involving the failure of reprocessed SUDs to make it a patient safety issue.

“This is something that the trade association for original manufacturers has created without answering a problem or satisfying a need in the state,” he said.

Kiani says although there is a monetary incentive, it’s not the bottom line.

“Certainly it’s financially motivated,” he said. “But at the same time we do care what happens to the patient, or otherwise we wouldn’t be here. If the goal is just to make money, there are other industries where you could make it.”

Sommer says the bill is similar to another law in the state involving car parts.

“Under Massachusetts law, an individual must provide consent if an aftermarket part is used in their vehicle, but they are not required to provide consent if a reused medical device is used in their body,” he said.

“While hospitals use reprocessed devices primarily in an effort to cut costs, this savings may come at the price of jeopardizing patient safety,” said Sommer.

And research shows that hospitals are indeed saving money with the practice: Estimates range from $200,000 to $1 million annually per hospital for EP catheters alone according to a General Accounting Office (GAO) report titled “Single-Use Medical Devices: Little Available Evidence of Harm from Reuse, but Oversight Warranted”.